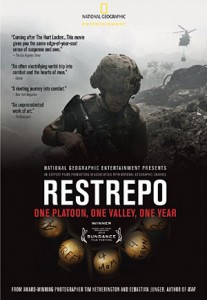

Tim Hetherington is a photographer and filmmaker who has been reporting on war for over ten years. A regular contributor to Vanity Fair, he is also a four time recipient of the press photo prize awarded by World Press. Along with author and journalist, Sebastian Junger, Hetherington has co-directed the new documentary, “Restrepo”, which premiered at Sundance this past season. I sat with Tim, a British subject who is based in New York City, sipping coffee and enjoying an especially lovely early summer day at a cafe just off West Houston Street.

AS: I know you and Sebastian both come from a war reporting background. How did you two meet and how did you come to the idea of making this documentary?

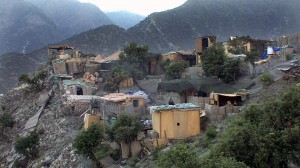

Tim Hetherington: Sebastian had the idea that he wanted to follow a platoon of soldiers for a year. At the time he had thought of it, no one had done it. It’s kind of surprising since the war on terror had been going on since 2001. He was looking around for a group of soldiers to follow and subsequently met a battle company, the 173rd Airborne in the Zabol Provence in Southern Afghanistan in 2005 and he really liked the guys. He liked those soldiers. So he wondered where they were again and it turns out they were in the Korengal Valley.

AS: They were the 2nd Platoon?

Hetherington: Yes, so they were in the Korengal and he knew he wanted to go out there. Originally, Sebastian had it in mind that he wanted to write a book. He has a relationship with ABC-News. He thought I’ll take a video camera, perhaps shoot some video, maybe make a film. The articles were being supported by Vanity Fair (both Junger and Hetherington are regular contributors to the publication). Vanity Fair teamed us up. So that’s how we ended up going to Afghanistan together. I don’t think either of us thought that this was going to turn into a full on feature length documentary. I mean, sure, make a TV film but a film like it’s turned out? No. When I first went out there I thought it was going to be a pretty quiet assignment. Go out with some guys, meet some village elders. You know, at the time the war was pretty focused on Iraq. Afghanistan seemed pretty quiet in my mind. Nothing prepared me for the level of fighting that went on.

AS: Ironically, you landed in the hot spot.

Hetherington: By the end of the film nearly 1/5 of all the fighting in Afghanistan was in the Korengal Valley. So, yeah, it turned out that way. We arrived at the time where this Valley had just become this epicenter.

AS: Then even though it was a potentially volatile spot, you perhaps unintentionally ended up where the story was.

Hetherington: Well, all journalists search for a story that tells a bigger story. I think if you are trying to make a visceral war film then the Korengal was the right place to be. We were at the heart of the storm , as it were, and it was a great place to make our work.

AS: So you went in without knowing how the project would end.

Hetherington: Yes, it was an organic process.

AS: How did you guys get clearance. It’s pretty remarkable. I was convinced that you gave the video cameras to the soldiers and spoke to them remotely from somewhere in Italy.

Hetherington: [Laughs] When reporters go on an embed with the military they sign a waiver, saying like, if I fall out of a helicopter I can’t sue them. I was never censored. I was never asked to show any images to the U.S. military. I was never told I couldn’t film something. I was never banned or controlled in any way. I was a bit surprised by that. I was expected that I would be. But I wasn’t. When you tell the military that you are going to do a documentary feature you fall under a different set of rules. So when we first went out there we didn’t know we were going to be making a feature length documentary film so we were under the traditional embed rules that reporters operate by. You sign when you go through Public Information Office at the Bagram Airbase. When we told them some months later that we were going to make a documentary we had to go by a different set of rules. You go through the U.S. press office in Hollywood. You sign a legal contract. This stipulates that before you go online you give the military a version of the final cut. They have 72 hours to review it and come back to the film maker regarding issues with any points that are covered in the contract. Those points are very innocuous. You can’t show overhead images of bases. It’s mostly to do with strategic things having to do with national security. You had to get permission from wounded soldiers to film them. Interestingly enough, we showed overhead images of bases and they didn’t raise the issue. So we sent them the rough draft and they came back to us with almost nothing. So showing dead soldiers and civilians was not a problem since it wasn’t covered in the contract. I think the question of censorship, the question mark comes out of the Bush Era. The war was so tightly controlled. Especially the relationship between the media and the right wing. To be honest, I’m a European. It was my first time dealing with the U.S. military. I was very surprised by the level of access we got. And I think that the military was surprised by the level of access we got as well. The embed system was misshaped by the Bush Era. I was the only reporter who lived behind rebel lines during the Liberian civil war. I was embedded in a rebel army. No one ever asked me about that embed system then.

AS: I understand.

Hetherington: I have reporter friends who have done tours of duty in Afghanistan. They’ve told me the longest they are with a group of soldiers is about three weeks. Friends of mine were on tour during Battle of Fellujah. Three weeks and they never saw the soldiers again. I personally managed to spend five months with one group of soldiers. The U.S. military doesn’t expect reporters to spend five months with one set of soldiers. The embed system isn’t designed for that. That’s why I think our film is different.

AS: You witnessed a soldier getting killed during the Rock Avalanche campaign. Obviously you’ve seen your share of blood. DId this war uniquely different in that aspect.

Hetherington: Personally or Afghanistan as a war?

AS: Either.

Hetherington: It’s difficult to not have a sense of deja vu with the Americans in Afghanistan. I’m a Brit and the British army has been there over a number of years. Not that long ago, 100 years. We have a sense of military history of there. The Russians were. A lot of people have been in Afghanistan. Then again, a lot of people ask us did our film end up taking on some of the politics. I will say outright: Afghanistan is not another Viet Nam. I mean, in Viet Nam there were 160,000 NVA (North Vietnamese Army) heavily armed with artillery. There’s probably 20 to 40,000 Taliban with small arms and rocket propelled grenades.. Viet Nam began with a lie: the Gulf of Tonkin. Afghanitan began because of Al-Qaeda were using it as a base for operations against the U.S. There are many reasons why Afghanistan is not another Viet Nam. But trying to control the insurgency within a large country does give a sense of deja vu.

AS: On a personal note? You mentioned over a span of fourteen months you were with them for five, right in the trenches. You mention in the press notes that you felt like family after some time. Witnessing these guys get injured or just feel that level of anxiety, how could you not become emotionally involved in the story. This must have been a very different experience for you as a war journalist.

Hetherington: You’re right. Sebastian and I did five months each, sometimes together and sometimes apart. The embed system means you spend a lot of time with people, so you identify with them. You get close to them. Even though you are physically embedded, it doesn’t necessarily means you’re emotionally embedded. But like any good documentary film maker I want to emotionally close to the subject. I seek to do that. I did get close to them and I did end up empathizing with them. And just because you get emotionally close to someone doesn’t mean you can’t remain honest and objective about what’s happening.

AS: Have you stayed in touch with the men?

Hetherington: Absolutely. They were the the first people we showed the film to. All the soldiers that were back from Afghanistan, we brought them and their wives to New York and showed them the rough cut edit.

AS: They didn’t go to Sundance to see it?

Hetherington: Funny enough, one of the soldiers, Misha Pemble Belkin, was in Little Rock recently for the festival there and picked up an award for the film. We weren’t there so he picked it up.

AS: Ultimately, what do you think separates Restrepo from other war documentaries that have come out recently?

Hetherington: Afghanistan and the previous wars on terror have been viewed through a very divisive party political lenses. And that hasn’t been helpful to the nation in trying to digest and understand what’s going on. A lot of films have been very politically based. And they’ve been obviously full of moral outrage. Now, if you ask me, am I anti-war, or if anybody in this room was anti-war, we’d all put our hands up. We all agree on that. As a piece of communication I think it’s more useful to not have divisive films but have films that bring soldiers, their families and their communities into a dialogue with the mainstream. Because usually the soldiers from those communities are cut off from that dialogue. And to not have it left wing or right wing politics underpinning the film. Restrepo is a film where we try to bring, what ever your views are, to understand what’s happening out there. And I think that’s probably what’s needed at this time. I think this country is ready for this type of film.

AS: In any case, almost anybody with a mind can sniff out an ideological agenda, no? And that can be insulting on some level. You can change more people with an honest objective film and let people make up their own mind about it.

Hetherington: To me “Restrepo” is the distillation of what I’ve noticed about men and war, and what I’ve wanted to communicate effectively about these ideas to people. I’ve spent many years trying to get people to think about West Africa. Liberia is a country I’ve lived in as a resident and that America has a long history with. The relationship goes back to slavery days. And in photography there’s just no use in showing pictures of dead Liberians. or violence against Liberians. It doesn’t work. You have to be smarter. For Restrepo I decided to focus on the sons of America. That’s the way I found was the most useful way to do it. There are very good reports covering the war and the Taliban but this is the way we chose to do it. I think it’s a good strategy. As I said earlier, I really do struggle with the ideas of strategy [in creating a story].

AS: As someone who pitches stories I assume that’s key.

Hetherington: We weren’t co-opted on “Restrepo”. We weren’t co-opted by an NGO. Many journalists become co-opted. We haven’t been. Now they can say we’ve been co-opted by the military. The left wing might thing we have been, but in fact the film doesn’t always show the soldiers in a great light. It raises questions about what we’re doing there. So we haven’t been co-opted and I think that’s important. Because there’s a lot of journalists in foreign countries who need access.

AS: I understand you have a new book coming out, Infidel?

Hetherington: Yes, Infidel is coming out in October. It’s being published by Chris Boot Limited. Photography books are a completely different business and Chris is a great. The book is again about platoon soldiers and their experiences. We even show a series on tattoos that they have across their chests. A lot of the soldiers have tattoos. They even had a tattoo gun up there. At Restrepo they had a tattoo gun and they’d tattoo each other.

Hetherington: Fighting and combat has quite a capture on the imagination. What’s really interesting, in the book I took a series of pictures of soldiers sleeping and they are quite vulnerable. To me, after a while, the fighting becomes quite boring. What was interesting to me was the inter-personal relations among the men and between us and the men. So the book really explores that in a way that I think a lot of war-oriented photography books do.

AS: I guess you could say that the book is not about war but about young men, about soldiers.

Hetherington: Well, in some way it is about the war machine. There’s been a lot of photo work about missiles and weaponry. But this is the war machine too. The way you make men bond. Do basic training together and put them on the side of a mountain together. And they would be killed for each other. That’s the war machine. And the book is about that.

AS: You do get that sense the film “Restrepo” that there’s nothing these guys wouldn’t do for each other. And you never loose that for the rest of your lives. And you see that in elderly veterans, old men, who talk with tears in their eyes about their brothers.

Hetherington: Yeah, right. Someone asked Sebastian recently if women could do this job. And he said well if the woman could carry 150 pounds of equipment on their backs then they could do it. And that’s kind of true but in another sense, is it just a male thing? Can women be as effective fighters as men? Do women form as close friendships as men? In that way men bond like we were discussing. It’s an interesting question.

Tim Hetherington’s photo essay book, Infidel, published by Chris Boot Limited, will be in bookstores October, 2010. Photos by Tim Hetherington, with an introduction by Sebastian Junger. Sebastian Junger’s book, War, published by Twelve, is currently available both in bookstores and online.