“Godard Mon Amour” is a funny, charming film about the brief marriage of nouvelle vague film director Jean-Luc Godard and the late actress Anne Wiazemsky, directed by Michel Hazanavicius, best known for directing 2011’s Oscar-winning “The Artist.” Originally released last year as “Redoubtable”, it has been renamed for its US release. (The original title refers to a radio story about a famous French submarine heard in the film. The name becomes an inside joke for the couple.) A remarkable pastiche, Godard fans will love the numerous homages to his films as well as the ironic use of soundtracks from them to cue certain scenes. For example, the music from his film “Contempt” plays during a late scene in which Godard visits his wife while she is in Italy acting in a film directed by Marco Ferreri (1969’s “The Seed of Man.”) His intense jealousy threatens their marriage in much the same way the scene did in “Contempt.” Hazanavicius has separated the film into chapters, much as Godard often does with his films, and has the couple occupying flats that look just like the ones lived in by couples in “A Woman is a Woman” and “Pierrot Le Fou.” A black and white sex scene is filmed in the same way as a similar sequence in “A Married Woman.” And it wouldn’t be a proper homage if the fourth wall wasn’t broken, with characters and narration addressing the audience.

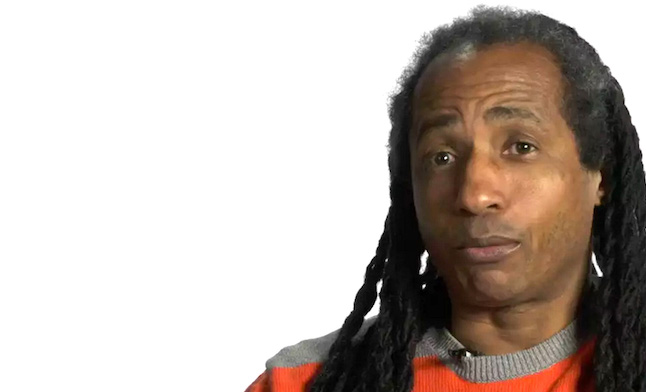

Louis Garrel (who is excellent) looks and sounds just like Godard. He perfectly delivers Godard’s self-doubting and provocative sloganeering, most humorously in a scene in which he tries to wriggle out of an offensive observation made before a group of students. Stacy Martin more closely resembles Godard’s first wife, Anna Karina, than she does Wiazemsky (whose book the film is based on). This choice informs the many scenes inspired by pre-’68 Godard classics and suggests that his attraction to Wiazemsky may have mirrored his own evolving artistic obsessions. Before this film, Martin was mainly known for her work in Lars Von Trier’s 2014 film “Nymphomaniac.” She was nude a lot in that film and, is just as often in this film, most notably in a scene referring to the famous opening of “Contempt” in which Bridgette Bardot’s derriere is presented as if it were a gift to the audience. (Godard did the scene in protest and wrote dialogue that turned it into something of a self-critique.) Martin is sublime as the long-suffering Wiazemsky, who despite her husband’s radical politics, is treated with the same posessiveness found in any bourgeouis marriage of the period.

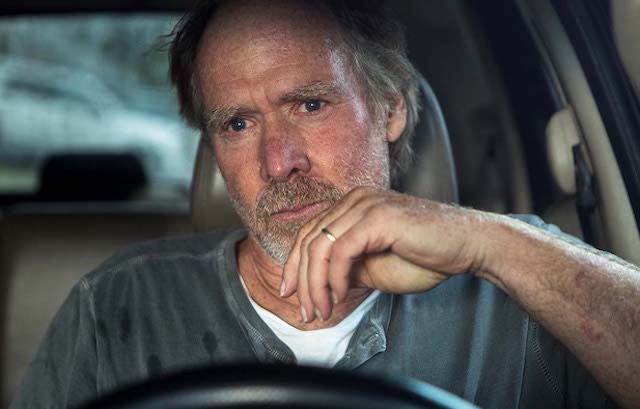

No one ever said Godard was a nice person and he is depicted at his most petulant here, insulting fans who —in a nod to “Stardust Memories”— wish he would make light, comedic films again. Portraying Godard and his May ’68 politicization as the necessary and self-willed destruction of an art hero (the death of that Godard) lends the film an unavoidable sourness, and serious Godard fans will feel obligated to tell their less informed friends that Jean-Luc is much, much more than a narcissistic jerk —though he is often that, to be sure— and continued to make important films for fifty years. This May is the 50th anniversary of the events of this film, and he is still alive and working.

“Godard Mon Amour” is a must-see for Godard fans or anyone who loves the French New Wave. It opens April 20 at the Quad Cinema in Manhattan, a week shy of the 50th anniversary of the May ’68 events the film depicts.