“By the Time it Gets Dark”, the new feature from Thai director Anocha Suwichakornpong, is the narrative equivalent of a leisurely stroll through an unfamiliar landscape. Characters from all walks of life in Thailand —from chamber maids and students to film actors and revolutionaries— appear, disappear, and reappear at random in scenarios centered around a female filmmaker’s research for a script about an aging female revolutionary. While this exploration of identity and roleplaying creates a surplus of vantage points for a colorful survey of Thai culture and history, Suwichakornpong uses the same tactics as an icon of Nordic cinema in crafting this journey.

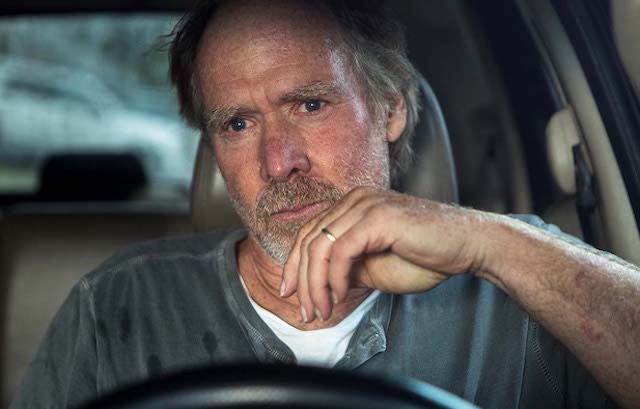

The film’s dreamy pace recalls the work of Nicolas Winding Refn. The Danish director’s films about criminals are contemplative, preferring to explore the moments when these psychopaths brood as opposed to whenever blood is shed. Think of “Drive”’s long shots of Ryan Gosling–captured from the front passenger’s seat–driving his car to the strains of pop music as neon colors bathe his face, and you will have a pretty good idea of how Suwichakornpong appropriates Refn’s pacing for a more pacifist film. In one scene, Suwichakornpong follows a lone woman as she arrives at her home. When she prepares to fry a single egg, the camera’s interest focuses on the wok more than the woman. This choice forces the viewer to follow the action of the sequence via the small breaks in the ambient noise soundtrack. The film in turn demands an understanding of a character’s surroundings in order to understand the character. This same deliberateness charmed audiences at Cannes in 2010, winning the Palme d’Or for Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s masterpiece “Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives.” Just like in that classic from a countryman, slow, methodical action in “By the Time it Gets Dark” lures and eventually charms viewers into following its unpredictable turns until the screen itself gets dark.

Nele Wohlatz’s “The Future Perfect” —winner of the Best First Feature prize at the 2016 Locarno International Film Festival— portrays a fascinating transformation that rests the film’s success squarely on the shoulders of lead actress Xiaobin Zhang. She plays Xiaobin, an 18 year-old recent Chinese immigrant to Argentina. During her time living with family in Buenos Aires, she will get a job at a deli, navigate a chaste romance with Indian computer programmer Vijay (Saroj Kumar Malik), and learn Spanish in stilted language classes with other Chinese immigrants.

Xiaobin’s first on-camera Mandarin —delayed until the film’s halfway point by obscuring her face or placing her out of the frame whenever she previously spoke the language— comes after an unexpected marriage proposal from Vijay. Xiaobin eloquently employs her native tongue to explain her reasoning for declining the proposal. While the Spanish-speaking Xiaobin is hesitant and awkward, she transforms into an exemplar of composure and self-knowledge in Mandarin, an accomplishment in modulation on Zhang’s part. The “possible futures” that Xiaobin imagines in the film’s final third suggest positive and negative paths for her life, and the actress adroitly swings between the emotional highs and lows the character experiences in these scenarios. Zhang’s significant range helps her deliver one of the most memorable performances at this year’s New Directors/New Films.

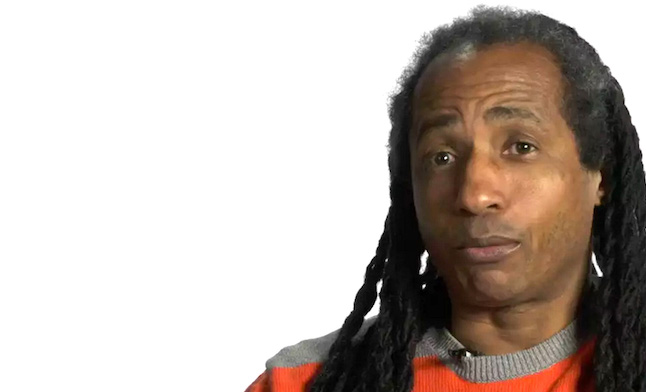

Christopher “Quest” Rainey and his wife Christine’a “Ma Quest” Rainey run Quest Studios, a hip hop recording studio in North Philadelphia. The film begins with their wedding. A low angle shot after the pastor declares them man and wife lets us see the drop panels and fluorescent lighting of the ceiling. This image becomes a visual motif repeated throughout Jonathan Olshefski’s “Quest,” portending the limits and challenges the Raineys will face during the eight years that cameras followed them.

Those eight years coincide with Barack Obama’s presidency, 2009 to 2016. The ascendance of the first African American president acts as a spine to the telling of the Raineys’ ups and downs. Campaign ephemera —including T-shirts and lawn signs— quietly appear throughout the film. Olshefski’s camera lenses a barbershop calendar for 2009 showcasing Obama with his wife and daughters, tying it to the film’s other narrative through-line: the importance of family.

Despite some hip hop performances shot in red lighting and occasional flare-ups of studio drama, “Quest” primarily explores Christopher and Christine’a’s trials as parents, and they face many in the span of the documentary. When the couple’s daughter PJ is struck in the eye by a stray bullet, the director wisely allows parental anguish to guide the narrative. Olshefski joins Christopher in returning to the corner where PJ was shot; the film physically retraces the steps taken that day in a scene that acts as a physical manifestation of a parent’s obsessive concern for his or her child. Ceding narrative control to Christopher —literally having him direct the camera’s attention to locations around the incident— draws the viewer into his grief in a way that makes PJ’s eventual recovery that much more rewarding.

However, the greatest threat to the Rainey family lies at the end of 2016 in the form of Donald Trump. Focusing so much attention on the Obama presidency makes our current president prominent in the contemporary viewer’s mind before The Donald even appears on a television screen. Olshefski shows Chris and Christine’a watching the speech where Trump decried the squalor of “inner city” life and asked African American voters, “What do you have to lose?” by voting for him. The director focuses on the Raineys as they simmer with quiet rage, assessing this palpable threat to their community. Christine’s —shaking her head in disapproval— says to the television, “You don’t know how we live.” “Quest” is a possible first step in making sure that Trump (and others like him who seek to deny communities their rights) might learn how people like the Raineys live.