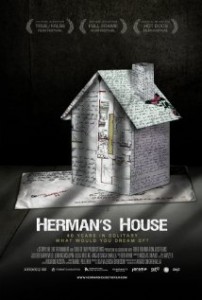

Anyone who cares about social justice surely knows about the sad story of the Angola Three. A new documentary, “Herman’s House“, which is having its New York premiere Wednesday night at the Harlem International Film Festival, powerfully states the case against prolonged solitary confinement and how one activist made a huge difference in the life of Herman Wallace. Wallace has been in solitary confinement in Louisiana’s Angola prison for 40 years, longer than anyone ever has been in the U.S. There are doubts about his guilt–the widow of the guard he is charged with murdering even has her doubts. And one can’t help but suspect that his involvement in the Black Panther chapter at the prison is why he still remains in solitary, rather than being in the general prison population.

Anyone who cares about social justice surely knows about the sad story of the Angola Three. A new documentary, “Herman’s House“, which is having its New York premiere Wednesday night at the Harlem International Film Festival, powerfully states the case against prolonged solitary confinement and how one activist made a huge difference in the life of Herman Wallace. Wallace has been in solitary confinement in Louisiana’s Angola prison for 40 years, longer than anyone ever has been in the U.S. There are doubts about his guilt–the widow of the guard he is charged with murdering even has her doubts. And one can’t help but suspect that his involvement in the Black Panther chapter at the prison is why he still remains in solitary, rather than being in the general prison population.

“Herman’s House,” directed by Angad Ballah, tells the story of New York artist Jackie Summell’s unique artistic response to Herman’s fate. She began writing and phoning Wallace and asked him to imagine the type of house he would like to live in instead of the six-by-nine-foot cell he has been in since 1972. This communication was the basis of an art installation she built, which included a life-sized model of his prison cell, plans and models of the dream house he imagined, and a timeline of his life. (You can see more documentation of the show at her website.) “The best activism,” Jackie says, “is equal parts love and equal parts anger.” Her outrage is matched by her rich friendship with Herman and her devotion to his cause extended after the installation (which she put on twelve times in various countries); she moved to New Orleans and began working to realize Herman’s dream of a house built to help troubled children.

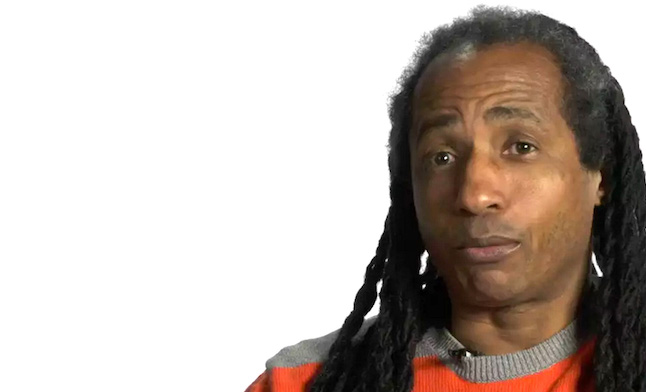

Herman appears in the film mainly via phone recordings with Jackie (sometimes interrupted by automated messages reminding the listener that the call “originates from Angola prison and maybe be monitored”). He is surprisingly thoughtful and upbeat for one who has spent four decades in conditions closer to physical and mental torture than imprisonment. He insists, for example, that Jackie interrupt her work on his project to attend to her cancer-stricken mother. A younger white ex-prison mate tells the story of how —during a brief hiatus in which Herman was returned to the prison dormitories-— he was taught compassion by Herman. How much of this compassion is the result of Herman’s Black Panther indoctrination, a fellowship he still values, instructing Jackie to put a drawing of a panther at the bottom of the pool next to his dream house?

The film is also about Jackie’s own history of living spaces, from the Long Island home she grew up in (“This was a violent house,” she says revisiting it after her mother’s death) to her New York apartment and then later in the home she relocates to in New Orleans. Herman’s sister Vickie shows Jackie the “shotgun shack” (since combined with an adjacent house) she and Herman grew up in. “Herman’s House” excels at making you think about the connection between space and socialization. How does space define destiny? Various prison architects evaluate the house plans of Herman’s house: it seems claustrophobic and doesn’t take advantage of either sunrise or sunset. This plan reflects the mindset of a man who has been imprisoned for a long time, one says.

Herman’s House will have its New York premiere Wednesday, September 19, 9PM at the opening night of the Harlem International Film Festival. Filmmaker Angad Bhalla will be in attendance for a post-screening Q&A. Tickets available with this link.