Tony Zierra’s documentary “Filmworker” tells the story of Stanley Kubrick’s long time and most trusted assistant Leon Vitali, who, for two decades, worked endless days for the maestro. What did he not do? He was an actor, dialogue coach, casting agent; he handled color timing and inventory of prints, created trailers and supervised marketing materials. The lists of tasks Stanley gave him every day to do was daunting. His children complain that his job meant he often neglected them. Vitali tells scary stories of his employer’s temper tantrums. So why did he do it? “I loved him,” Leon simply says.

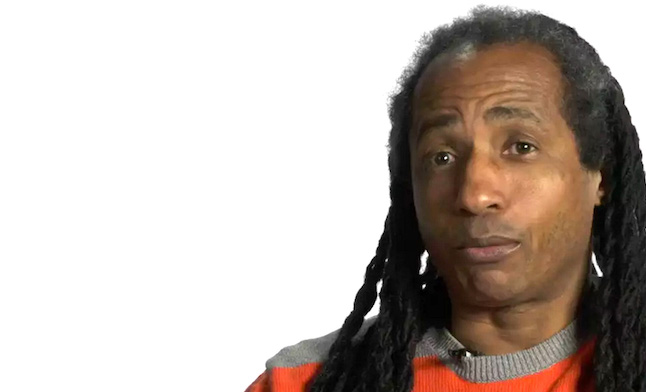

A successful actor, Vitali was cast as Lord Bullington in Kubrick’s 1975 film “Barry Lyndon.” He was so impressed with the director he asked to work for him in any capacity in the future. Kubrick hired him to cast the important role of Danny Torrance in his 1980 film “The Shining.” Vitali also cast the two girls in the hallway scene of that horror classic. The script called for only one girl but Vitale was reminded of a famous Diane Arbus photo with two sisters and Kubrick, who started out as a photographer, loved the idea. This began two decades of work that gave Vitale unique access to the making of Kubrick’s last three films. It also took a huge toll on his health; the haggard Vitali looks much older than his 69 years.

After Kubrick’s death in 1999, Vitali supervised the completion of “Eyes Wide Shut” and worked for years ensuring the quality of future releases of Kubrick films. Despite his dedication, he was not even consulted for the huge 2012 Kubrick show at the Los Angeles Center for Modern Art. (Also curiously absent from the documentary are any interviews with Kubrick’s wife or daughters.) Even though he was slighted, he conducted tours of the show for groups of friends and students.

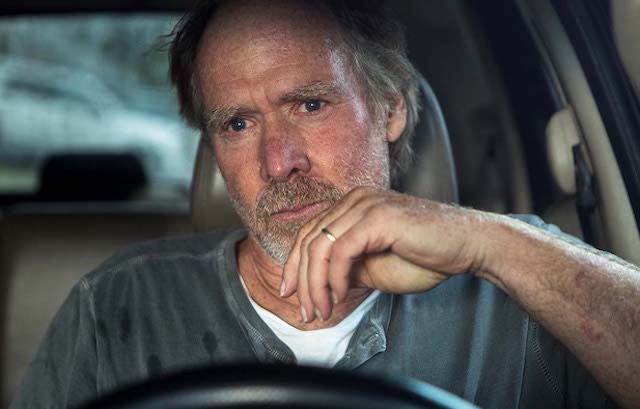

Despite his close association with the director, Vitali insists upon calling himself a filmworker, a term he applies whenever asked for his occupation. The film is, in part, a celebration of the immense work and dedication everyone on a film crew provides in the service of art. Ingmar Bergman once compared film production to the building of a cathedral. But few filmworkers are as loyal as Vitali. The recently deceased R. Lee Ermey noted that he is too selfish to have dedicated 30 years to the art of one man. Ermey gives Vitali credit for improving his performance as the drill sergeant in “Full Metal Jacket.” Another actor, Tim Colceri, was originally cast but Ermey, hired as a technical advisor, campaigned for Vitali much to the first actor’s displeasure. (Colceri is still angry that Kubrick didn’t fire him in person. At the time, he dispatched Vitali with a letter, offering Colceri a much smaller, though memorable part as the door gunner of a helicopter.)

Kubrick is, of course, famous for his perfectionism but this is the first time I’ve heard someone go in to great detail about how voluble he was, and Vitali was often the target of Kubrick’s scorn. Vitali speculates that his patience with his employer owes something to his experience with his own father, a temperamental man whom he nevertheless loved.

Kubrick is, of course, famous for his perfectionism but this is the first time I’ve heard someone go in to great detail about how voluble he was, and Vitali was often the target of Kubrick’s scorn. Vitali speculates that his patience with his employer owes something to his experience with his own father, a temperamental man whom he nevertheless loved.

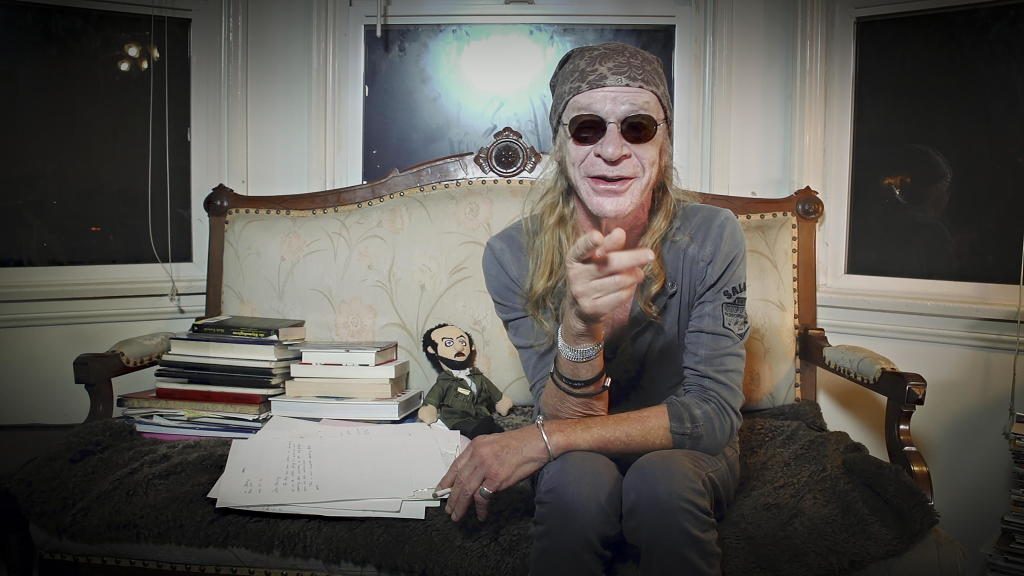

Zierra’s documentary is a must-see for any Kubrick fan or true cinephile. The only Kubrick doc with more insight into the director may be Jon Ronson’s 2008 film “Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes”. Zierra has done a terrific job of capturing the day-to-day exhaustive work performed by Vitali and a others, all in the service of masterpieces directed by the man Vitali considered the most important film director of the twentieth-century. Who can argue?

Filmworker opens Friday at the Metrograph in Chinatown with director Tony Zierra and Leon Vitali in person. The documentary will play along with a retrospective of 8 Kubrick classics, all screened in glorious 35mm.