At first glance, Jet Leyco’s “Matangtubig” (“Town in a Lake”) appears to be the result of filtering David Lynch’s sensibilities through the culture of the Philippines. The plot –focused on the rape and murder of a female high school student and the disappearance of another in a small town– bears more than a passing resemblance to the story of Laura Palmer in “Twin Peaks”; the fact that both girls are represented by framed photographs in the media hysteria that ensues calls to mind Laura’s ever-present homecoming picture. Just like in Lynch’s television masterpiece, the crime is merely a pretense to explore general aspects the town, including school life, political maneuvering, and law enforcement. Leyco even pays homage to Lynch’s enthusiasm for strobes as scenes that suggest a meeting between two worlds —law-abiding and criminal, earthbound and otherworldly— are bathed in a red light.

At first glance, Jet Leyco’s “Matangtubig” (“Town in a Lake”) appears to be the result of filtering David Lynch’s sensibilities through the culture of the Philippines. The plot –focused on the rape and murder of a female high school student and the disappearance of another in a small town– bears more than a passing resemblance to the story of Laura Palmer in “Twin Peaks”; the fact that both girls are represented by framed photographs in the media hysteria that ensues calls to mind Laura’s ever-present homecoming picture. Just like in Lynch’s television masterpiece, the crime is merely a pretense to explore general aspects the town, including school life, political maneuvering, and law enforcement. Leyco even pays homage to Lynch’s enthusiasm for strobes as scenes that suggest a meeting between two worlds —law-abiding and criminal, earthbound and otherworldly— are bathed in a red light.

Leyco’s reverence for the work of the American master also plays a role in shaping his cinematic grammar, but it is in this realm that his personal style shines through. Like Lynch, the Filipino director plays with time, alternating the film’s pacing to keep the viewer on his or her toes or to heighten a sense of dread. His scene transitions in particular can be jarring; many scenes end by suddenly cutting to another scene or to a black screen that lingers silently for what could feel like a few seconds too long. These transitions work well, though, in drawing the viewer into the frenzy surrounding the search for the killers.

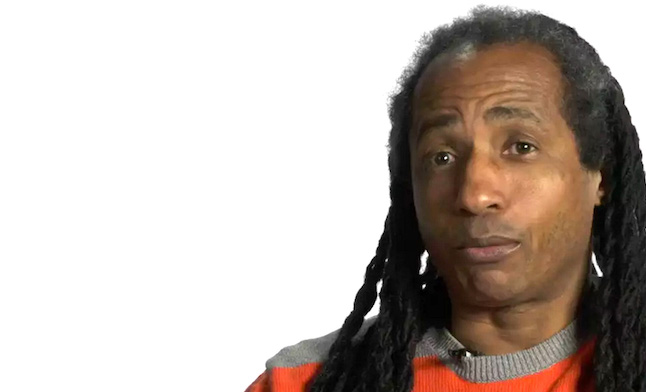

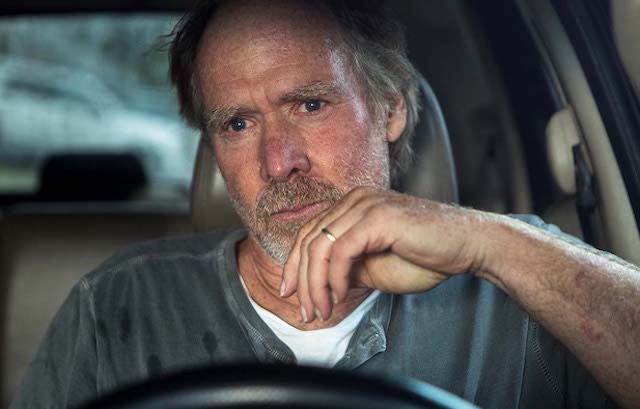

Lance Raymundo’s Benny —a reporter from out-of-town— emerges as the physical embodiment of this frenzy. He is the ultimate interloper, arriving in Matangtubig to exploit tragedy for ratings. Leyco brilliantly conveys Benny’s disconnect from the pain and trauma of the incident through his camera work. Several shots in the film show the reporter recording video segments for broadcast, and Leyco’s typically employs long shots in these scenes. This vantage point allows the viewer to see a frenetic Benny dwarfed by his surroundings as he enthusiastically describes the dirty particulars of the crime. We also see what others in the area are doing as he speaks. In one scene, a villager intrudes on the frame while transporting materials down a jungle road; in another, a bored cameraman stares despondently in the opposite direction of the reporter. All of these shots portray Benny as a chaotic abnormality in a peaceful environment, establishing him as a credible threat to the town’s equilibrium when he learns a fact about the murder that is salacious but not particularly relevant to solving it.

While Leyco forges a stylistic path apart from Lynch, “Matangtubig” would have been a greater success if it mirrored Lynch’s impeccable skill at crafting a puzzle box narrative. In “Twin Peaks” and films like “Mulholland Drive” and “Inland Empire”, Lynch presents set pieces apart from the main action, absurd dialogue readings, and oddball characters that might appear discordant on the face of things. However, everything makes sense if you simply approach it at the most literal level possible and build from there. For instance, when the Man from Another Place declares, “I am the arm,” in “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me“, the mystery makes the most sense if you take him at his word that he was an arm at one point. Leyco’s visual non-sequiturs —including lithe shadow giants, a schoolgirl with whited out eyes, and alien police officers— never cohere into a meaningful whole, depriving the audience of either a satisfying narrative or a metaphor-focused observation about the world at large. By walking in the footsteps of profound cinematic accomplishments, Leyco simply accentuates by comparison Matangtubig’s failure to achieve relevance outside of its scant 87 minutes.

While Leyco forges a stylistic path apart from Lynch, “Matangtubig” would have been a greater success if it mirrored Lynch’s impeccable skill at crafting a puzzle box narrative. In “Twin Peaks” and films like “Mulholland Drive” and “Inland Empire”, Lynch presents set pieces apart from the main action, absurd dialogue readings, and oddball characters that might appear discordant on the face of things. However, everything makes sense if you simply approach it at the most literal level possible and build from there. For instance, when the Man from Another Place declares, “I am the arm,” in “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me“, the mystery makes the most sense if you take him at his word that he was an arm at one point. Leyco’s visual non-sequiturs —including lithe shadow giants, a schoolgirl with whited out eyes, and alien police officers— never cohere into a meaningful whole, depriving the audience of either a satisfying narrative or a metaphor-focused observation about the world at large. By walking in the footsteps of profound cinematic accomplishments, Leyco simply accentuates by comparison Matangtubig’s failure to achieve relevance outside of its scant 87 minutes.