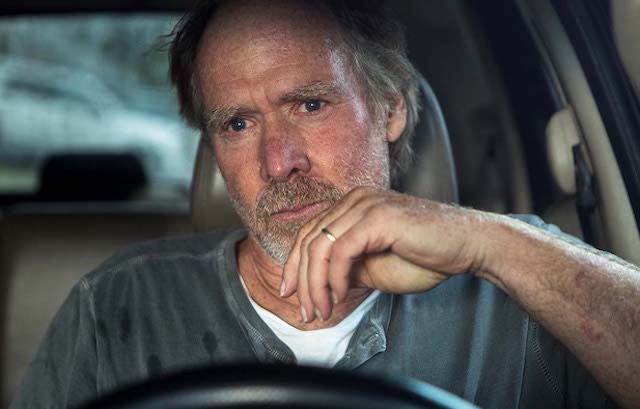

A simple disagreement with a mechanic about fixing his girlfriend’s car led to the shooting death of William Ford Jr. on April 7, 1992. After the Suffolk County District Attorney’s office on New York’s Long Island showed more interest in investigating the African American victim than the white defendant, a grand jury declined to indict. William Ford was treated like another black body destroyed and discarded by a prejudiced justice system.

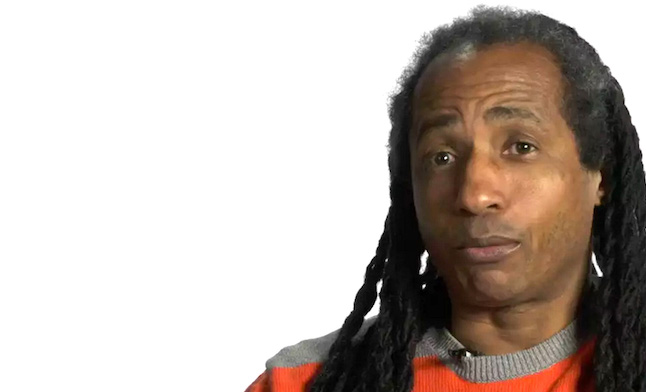

Screening as a part of New Directors/New Films, “Strong Island” —a documentary from William’s sibling Yance Ford— explores the circumstances surrounding the terrible evening. In an attempt to put some attention on his brother’s story, Yance lenses his own black body in ways that brings William’s murder back into focus.

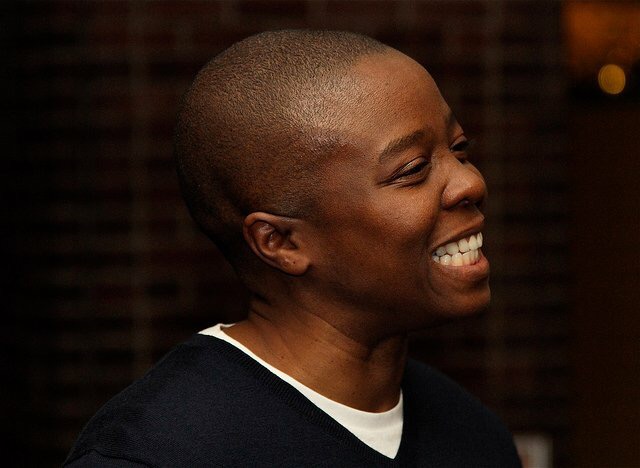

Yance’s face —round with a small scar stemming from the left side of the bottom lip— often faces the camera in a close-up. The background is dark black, and little below the director’s chin is visible, isolating his face in the frame. This stance is confrontational, setting the tone for a story seeking to challenge an authoritative account of events. In a statement at the start of the film that gives us a pretty solid understanding of what’s to come, Yance lets the audience know, “If you’re uncomfortable with me asking these questions, you should probably get up and go.”

To accompany shots of an almost disembodied head, the director’s voice animates the story of William’s life and the circumstances leading up to his death. Yance reads his brother’s autopsy report in a cold, clipped cadence, merely stating the rudimentary facts behind the devastation. When family members —including Yance’s mother and sister— discuss their own experience of learning about the murder, Yance delivers his own account from a printed piece of paper, needing this aide to describe an event he has likely replayed hundreds of times in his mind. These readings come into play when the director must recall the most emotionally painful aspects of the story; paper and print provide necessary distance for both Yance and the audience, which could be too emotionally overwhelmed to continue with the story without this clever technique.

The most prominently showcased part of Yance’s body is his hands. Like most documentaries recounting past events, the film features photographs of subjects—in this case the Ford patriarch, matriarch, and children—throughout their lives. Instead of merely presenting high quality scans of the images, Yance shares them via a shot of the pictures being arranged on a white surface. Photographs are moved to the center of this white surface, straightened, and situated in front of the lens. Here Yance makes a strong statement on the role of the documentary director who is also a subject. He fully acknowledges that his involvement creates subjectivity and that his hand(s) will be shaping the flow of the narrative. By acknowledging this, documentary purists in the crowd can clear their minds of any concerns regarding subjectivity and learn about the short life of this young man.

These techniques form an array of visual metaphors that allow the director to reclaim the life and body of his brother from the tragedy. The film’s final shot is a close-up static image of William’s face slowly fading into view on a black background. There are times when the basic shape and composition of the image recalls Yance’s own confrontational close-ups. After Yance’s noble efforts and persistence in this heart-wrenching documentary, William Ford will be remembered.