Filmwax Radio blogger Herbert Gambill’s 3rd dispatch from the New York Film Festival press & industry screenings. The Festival runs from Friday, September 26th through Sunday, October 12th.

Filmwax Radio blogger Herbert Gambill’s 3rd dispatch from the New York Film Festival press & industry screenings. The Festival runs from Friday, September 26th through Sunday, October 12th.

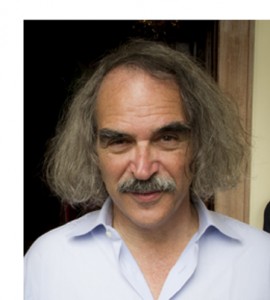

The plot of Eugène Green’s “La Sapienza” brings to mind Rossellini’s “Voyage to Italy.” In that 1954 film an estranged couple’s visit to Pompeii provided something of a rekindling of their love. In Green’s film a successful middle-aged French architect, Alexandre (played by Fabrizio Rongione, who also stars in the Dardenne brothers’ “Two Days, One Night,” another film in this year’s NYFF main slate), depressed by changes ordered by a client, travels with his wife Alienor (Christelle Prot Landman) to view the works of one of his heroes, the Roman Baroque architect Francesco Borromini. The couple, whose relationship has been running cold for many years, first visits Borromini’s birthplace, Ticino, in the Italian-speaking southern part of Switzerland, by Lake Maggiore, where they meet two teenage siblings who make a huge impression on them. Goffredo (Ludovico Succio) wants to study architecture himself; his sister Lavinia (Arianna Nastro) suffers from dizzy spells perhaps induced by her fear of being separated from her brother. Though Alexandre gives Goffredo a chilly initial reception, his wife talks him into proceeding to Rome with him, leaving her to tend to an ailing Lavinia.

Alexandre takes his new apprentice to several examples of Borromini’s work, presenting lectures that often end with Green panning his camera up and around, providing stunning panoramas of the architectural features. Goffredo’s unschooled but perceptive ideas about the profession (“spaces are nothing but emptiness, which needs to be filled with light and people”) gradually soften Alexandre. He even declares at one point that he himself is now the student.

Alexandre takes his new apprentice to several examples of Borromini’s work, presenting lectures that often end with Green panning his camera up and around, providing stunning panoramas of the architectural features. Goffredo’s unschooled but perceptive ideas about the profession (“spaces are nothing but emptiness, which needs to be filled with light and people”) gradually soften Alexandre. He even declares at one point that he himself is now the student.

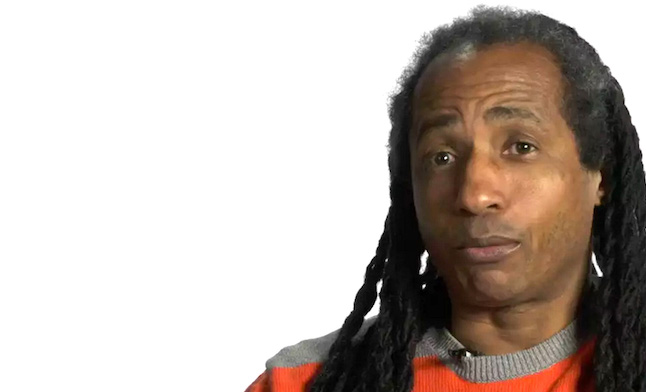

Green is also a theater director, with a strong interest in French Baroque theatre, in representing historically correct diction and the period’s use of declamation–taking on the persona of an ancient person to create a unique points of view, a technique used in one sequence here that seems perhaps too on-the-nose. Green himself appears in one scene as an Iraqi exile who identifies himself as a Chaldean Christian who speaks Aramaic! The use of multiple languages in the film and Green’s employment of shot/counter shot dialogue scenes in which the camera is placed successively closer to the actors as they speak directly to the camera, is fascinating at times. But at other times it makes the film seem like a foreign language instruction video. Some broad humor late in the film lightens the mood and reminds us of how insular the story has been up to that point. The last Borromini masterpiece the two men visit is Saint Yves at La Sapienza Church. (Sapienza means wisdom in Italian.) A bravura visual tour of the interior of that space sums up the intellectual ambitions of this odd, unique, masterful film about the humanistic aspects of architecture and what it can tell us about life, love and community.

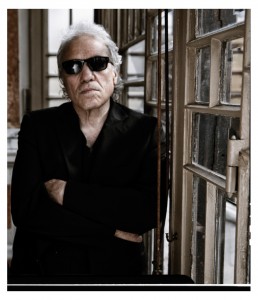

Abel Ferrara’s “Pasolini” opens with the titular Italian director (Willem Dafoe, a revelation), just back from a visit to Stockholm, sitting in a sound mixing session for what would be his last film, the scandalous “Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom.” A French journalist asks him which of his many monikers —poet, director, critic, marxist— he prefers. He answers, switching momentarily into French, “Dans le passeport j’écris simplement ‘écrivain’.” (On my passport I write simply writer.)  Ferrara regular Dafoe is excellent as the controversial poet-turned-filmmaker, who was murdered in 1975.

Ferrara regular Dafoe is excellent as the controversial poet-turned-filmmaker, who was murdered in 1975.

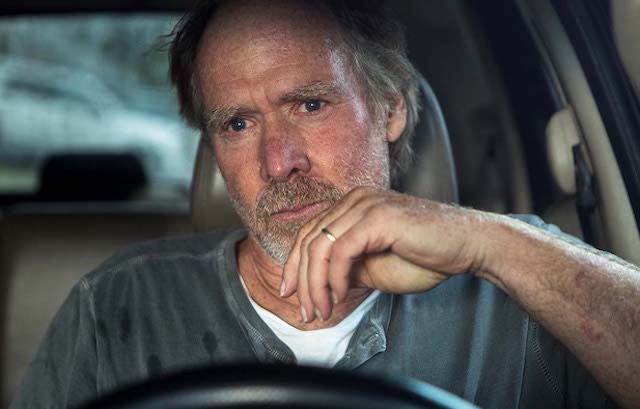

It’s thrilling to watch Dafoe as Pasolini, wearing stylish sunglasses, a close-fitting leather jacket, driving the streets of Rome in his Alfa Romeo (at one point, curiously, to the sound of “Poke Salad Annie”!), entering closed restaurants through the kitchen door, typing pages on his Olivetti and fielding questions from another journalist whom I suspect was modeled after Gideon Bachmann, a Pasolini friend who wrote regularly for the U.S. publication Film Quarterly in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Upset by the middle-class composition of the rebels who made up much of the political unrest in Italy in the early ‘70s (the “days of lead”) and disgusted by the rise of consumerism, Pasolini remarks “we are all in danger.” We see Pasolini living in his Rome apartment, with his beloved mother, his personal assistant (played by Dafoe’s wife, Giada Colagrande) and Ninetto Davoli, an actor friend and ex-lover who appeared in several of his films. The real Davoli appears in one of several fantasy sequences used to illustrate passages of a story Pier Paolo was working on in his final days.

These do illustrate some aspects of Pasolini’s style and imagination but are often a distraction rather than an enhancement to the main narrative.  Maria de Medeiros (“Henry and June,” “Pulp Fiction”) gives a lovely performance as Laura Betti, an actress friend who appeared in seven Pasolini films and later made a documentary about him. Betti has returned from a shoot in Yugoslavia with presents, funny stories about dubbing the devil for the Italian version of “The Exorcist,” and a demonstration of how communists dance.

Maria de Medeiros (“Henry and June,” “Pulp Fiction”) gives a lovely performance as Laura Betti, an actress friend who appeared in seven Pasolini films and later made a documentary about him. Betti has returned from a shoot in Yugoslavia with presents, funny stories about dubbing the devil for the Italian version of “The Exorcist,” and a demonstration of how communists dance.

The scene of Pasolini’s murder, after picking up a rent boy and taking him to the beach at Ostia near Rome, is effective but somewhat overlong. The details of his murder on November 2, 1975 (oddly, Ferrara includes a close up of a calendar page three days later in the film’s final shot) are still disputed. Initially, the 17-year-old male prostitute he picked up was charged with bludgeoning him to death and running him over with his own car. But he later claimed three locals committed the murder, and this is the version Ferrara shot. I wish Ferrara had begun with the murder and flashbacked to a day or two before and had not indulged so much with the fantasy sequences. Still, this is one of Ferrara’s best films, and a good, short introduction for a generation of viewers, most of whom will be unfamiliar with the great Pasolini.