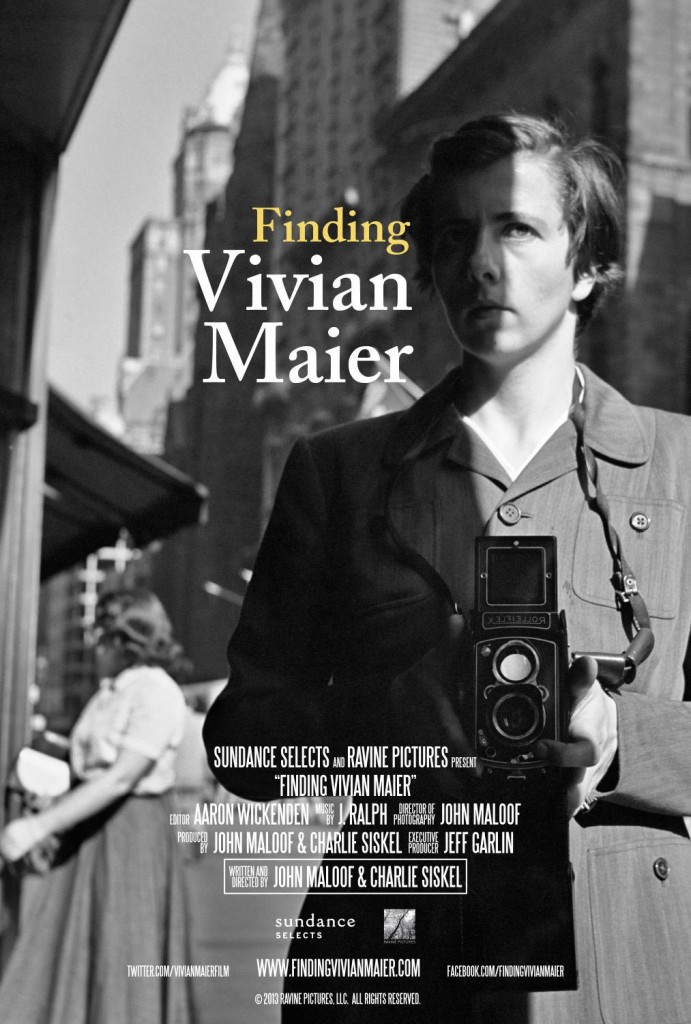

It’s the stuff of art history legend. In 2007, Chicago real estate agent and Americana collector John Maloof purchased a box of negatives at an auction for about $400 but had no idea what he found. He scanned some of them and only then realized what a treasure trove of incredible street photographs he had come across. Taken in Chicago and elsewhere over the middle decades of the 20th Century, the number of images ran into the tens of thousands. But who took them? His search for the photographer and the answer to why she never exhibited her work is the thrust of this fascinating and visually enthralling documentary directed by Maloof and Charlie Siskel (“tosh.O”),“Finding Vivian Maier.”

It’s the stuff of art history legend. In 2007, Chicago real estate agent and Americana collector John Maloof purchased a box of negatives at an auction for about $400 but had no idea what he found. He scanned some of them and only then realized what a treasure trove of incredible street photographs he had come across. Taken in Chicago and elsewhere over the middle decades of the 20th Century, the number of images ran into the tens of thousands. But who took them? His search for the photographer and the answer to why she never exhibited her work is the thrust of this fascinating and visually enthralling documentary directed by Maloof and Charlie Siskel (“tosh.O”),“Finding Vivian Maier.”

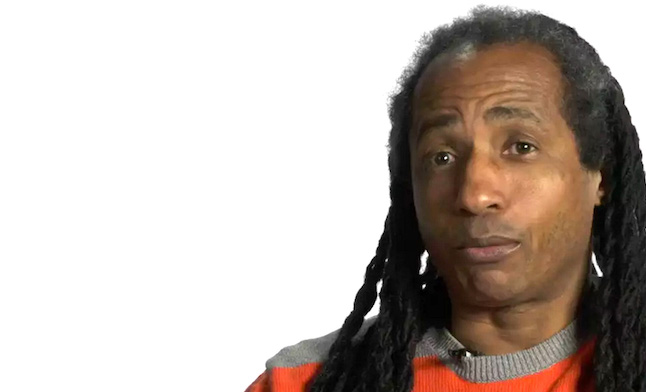

Joel Meyerowitz, famous for his own large format color photography, points out that the pictures show a real eye, and compares them to the work of greats like Helen Levitt, Robert Frank and Atget. But, as another interviewee puts it, the story of the photographer is even more interesting than the photos.

Vivian Maier worked as a nanny for most of her life. This, as one of her past employers observed, provided her with both housing and enough free time to take pictures. Which she did. Over 100,000 to be specific! But she also had a dark side, according to several of her former charges. She wasn’t above force feeding a child and dispassionately photographed another after they were injured in a minor car accident. Vivian never married and was an obsessive hoarder of newspapers. She loved collecting dark news stories that validated her sense of the folly of life; one compassionate ex-employer says with tears in her eyes, after recalling having to fire her. She was stern, private, and often difficult. A linguist who met her claims her French accent was fake. (“The vowels were too long. My master’s thesis was on French vowels.”) She had an obsessive fear of men that suggests some prior mistreatment and may have suffered from undiagnosed mental illness. She avoided doctors. “The poor can’t afford to die,” she said.

By the time Maloof discovered that Maier took the photos it was too late; she died at the age of 83 in 2009, poor and alone in a Rogers Park apartment paid for by a couple of the children she used to look after. Maloof, who is in his late twenties, devoted himself to the task of archiving and promoting his discovery. He managed to locate almost everything she left behind, including hundreds of rolls of undeveloped film. His dual role as part of the story —the film follows Maloof on the trail to solving the mystery— and director, has raised some critics’ eyebrows but I think that is negligible. (“I wish I had discovered her photographs myself instead of you,” one interviewee ruefully observes with a wink. Maier was also the subject of a short documentary that aired on the BBC last year and will no doubt be studied in monographs and other films for years to come.

One of the chief delights in the film, which is full of fascinating material and unfolds somewhat like the kind of engrossing stories Errol Morris is known for, is the awe-inspiring tableaux of Vivian’s boxes: negatives, clippings, receipts, buttons, cassette tapes, 8-mm films. Indeed, enough material for a whole Maier museum! It’s tragic that she never got any recognition until a mere few months after she died, of course, yet more than one of her friends says in the film that she never sought fame or would know how to handle it. Sure, if Elvis had just stashed his songs away in a box and died penniless and unknown he might have lived longer, but this is a cruel calculus–art is about sharing, not hoarding. One gallery owner says he wasn’t ready to show posthumous work when offered some of Maier’s work. “It wouldn’t be a good fit,” he explains. The discovery of unpublished artists after death —just like the art of the insane— is something of an embarrassment to the art world no matter whose fault it is. Why, we might ask, should we pay attention to the work of some hipster with a good agent when the homeless man with a sketch pad might be the next Van Gogh?

One of the chief delights in the film, which is full of fascinating material and unfolds somewhat like the kind of engrossing stories Errol Morris is known for, is the awe-inspiring tableaux of Vivian’s boxes: negatives, clippings, receipts, buttons, cassette tapes, 8-mm films. Indeed, enough material for a whole Maier museum! It’s tragic that she never got any recognition until a mere few months after she died, of course, yet more than one of her friends says in the film that she never sought fame or would know how to handle it. Sure, if Elvis had just stashed his songs away in a box and died penniless and unknown he might have lived longer, but this is a cruel calculus–art is about sharing, not hoarding. One gallery owner says he wasn’t ready to show posthumous work when offered some of Maier’s work. “It wouldn’t be a good fit,” he explains. The discovery of unpublished artists after death —just like the art of the insane— is something of an embarrassment to the art world no matter whose fault it is. Why, we might ask, should we pay attention to the work of some hipster with a good agent when the homeless man with a sketch pad might be the next Van Gogh?

“Finding Vivian Maier” premieres March 28th in NYC and LA at their respective IFC Theaters. Coinciding with the film’s release is the book “Vivian Maier: Self-Portraits.” The documentary also features a good, but perhaps too upbeat, musical score by “Chasing Ice” composer J. Ralph.