Directed by David Hoffman

Directed by David Hoffman

Produced by Jay Walker, Eric Reid, David Hoffman & John Vincent Barrett

Written by Hoffman & Paul Dickson, based on the book Sputnik: The Shock of the Century by Dickson

Edited by John Vincent Barrett

Released by History Films/Balcony Releasing

USA 87 min. Rated G

Narrated by Liev Schreiber

One of the more compelling lessons taken from David Hoffman’s new documentary, “Sputnik Mania”, is how the space race was as much a part of the Cold War as it was any other facet of mid-20th century popular culture. As soon as satellite technology was developed, it was immediately co-opted for the purposes of weapons proliferation by both the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

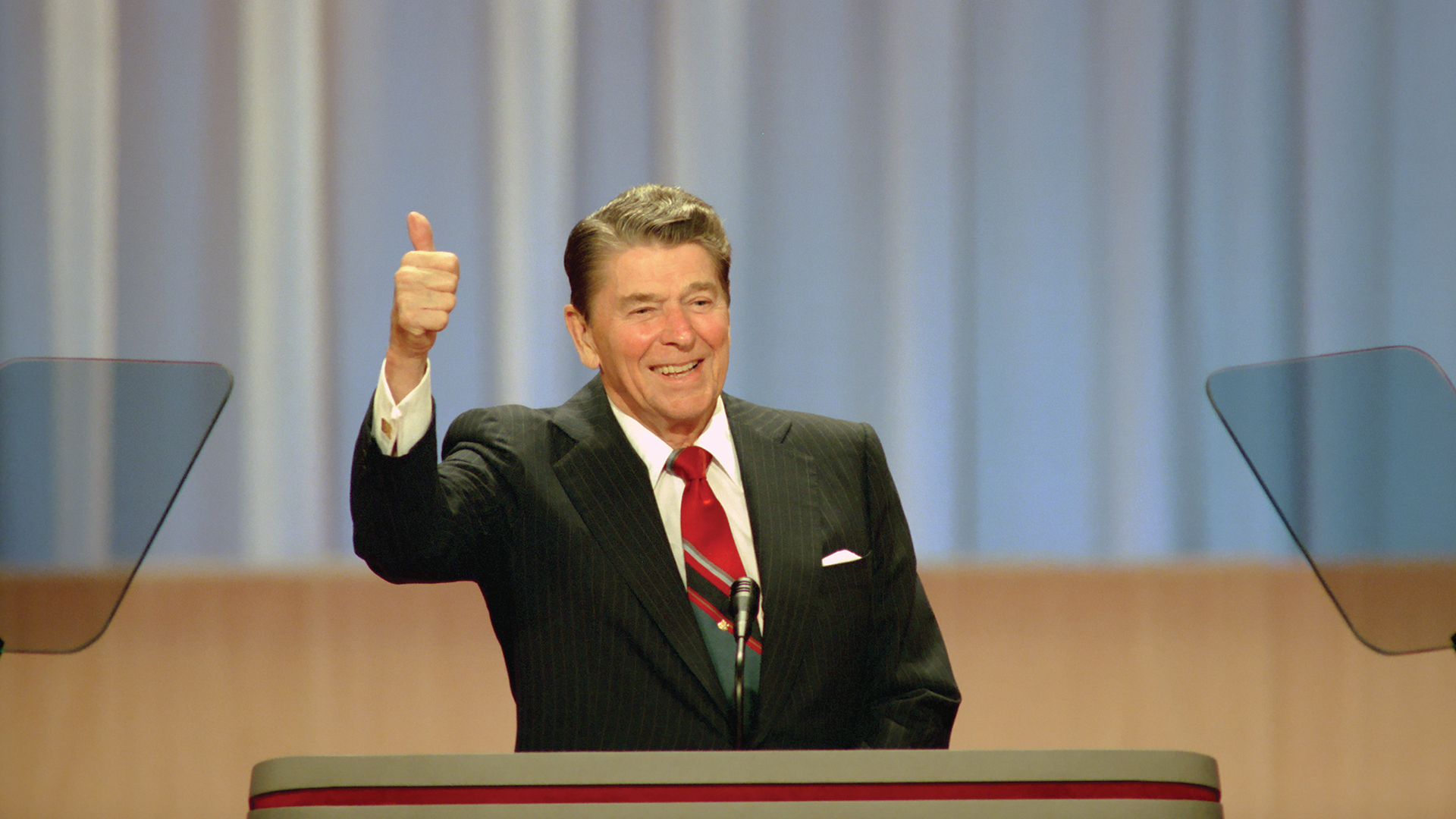

Based on Paul Dickson’s book Sputnik: The Shock of the Century, “Sputnik Mania” effectively illustrates the extremes of American fear and paranoia after the Soviets launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957. There are obvious parallels to be drawn between 1950’s Cold War America and this country 50 years later; between the fears of Al Qaeda today to the Soviets back then, for instance. Another parallel, and one that is ultimately quite ironic, is that the president was another conservative Republican who also took an unpopular military position that nearly jeopardized his reputation. The difference: Dwight D. Eisenhower, a former army general and World War II hero, was an outspoken critic of weapons proliferation.

Watching footage of the president’s speeches makes you pine for the days when our presidents had substance, intelligence, and perhaps most importantly, prudence. Eisenhower stood his ground while various members of Congress, grabbing the opportunity into tap in the country’s fears, argued for besting the Reds at any costs. Familiar images of school children “ducking and covering” under their desks are less amusing in this context than usual. The film, finely edited by John Vincent Barrett, convincingly shows how perilously close we were to a full-scale nuclear confrontation.

Humor, however, does play a role here but mostly in the ironic delivery of one of its primary interview subjects, Sergei Khrushchev, son of the late Soviet premiere. His intelligent, albeit droll, perspective anchors the film through a thick Russian accent and twinkling blue eyes.

The film ultimately ends with an amazing symbolic act by Eisenhower, one both simple yet profound, an event that seems to be practically lost amidst the footnotes of American history. Eisenhower, reputation somewhat tarnished, pulled off a feat that cut through the bunker mentality of the day, yet was criticized as an outlandishly expensive publicity stunt; he used satellite technology to broadcast a Christmas message of peace to the world. It would be the first time a satellite would be used as a communication device, and this was the message the world heard through radio:

“Through the marvels of scientific advance, my voice is coming to you via a satellite circling in outer space. My message is a simple one: Through this unique means, I convey to you and all mankind America’s wish for peace on Earth and goodwill toward men everywhere.”