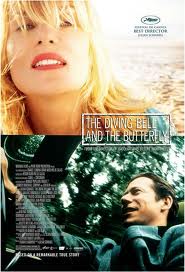

Directed by Julian Schnabel

Directed by Julian Schnabel

Written by Jean-Dominique Bauby

Screenplay adapted by Ronald Harwood

Cinematography by Janusz Kaminski

Edited by Juliette Welfling

Original Music by Paul Cantelon

Cast: Mathieu Amalric, Olatz Lopez, Marie-Josée Croze & Emmanuelle Seigner

[Article originally appears: http://www.rabbireport.com/archives/2007/09/nyff-07-review-3.htm]

The life of Jean-Dominique Bauby is at once tragic and inspirational and in the very capable hands of director Julian Schnabel, with “The Diving Bell and The Butterfly”, his story comes to the screen in a most moving and artful way. We learn through early dialogue and flashback that Bauby has suffered a major stroke and that coming out of a coma he awakens in a state referred to as locked in syndrome. Actor Mathieu Amalric (Munich) plays Bauby, editor of Elle magazine and a major player in 1990s Paris social circles. After his stroke, Bauby becomes all but incapable of communication, as he is unable to speak or move, with the exception of his left eyelid.

In the film’s first 20 minutes or so we are Bauby, the camera playing the role of his functioning eye. Seeing that Bauby’s entire world has been internalized, it’s an inspired device, executed perfectly by Schnabel and his DP Janusz Kaminski (“Saving Private Ryan”, “Schindler’s List”). Initially overwhelmed by a feeling of claustrophobia – imagine wearing a neck brace and an eye patch while lying motionless in a hospital bed, unable, even, to swallow – we quickly appreciate having Bauby’s thoughts as voiceover. In what some might see as a cruel stroke, his mental acuity is left intact, but many of his early thoughts are sarcastic and witty, providing some relief from the tension.

After a while the p.o.v. does shift which I thought might prove jarring to the narrative. In switching perspective you are pulled out for a moment, aware that the movie is being filmed and directed. But it’s not long before you’re back on board. This process is certainly helped by a couple of exquisitely lovely women: physical therapist Marie Lopez (played by Schnabel’s wife, actress Olatz Lopez Garmendia) and speech therapist Henriette Durand (Marie-Josée Croze). [There is one unforgettable scene involving her tongue which remained with this viewer long after the credits rolled.]

While he is naturally bitter and desperate at first, Bauby eventually learns – in some of the more beautiful moments of the film – how his imagination can set him free. In an ingenious sequence, he learns to communicate using only his one working eye. As his speech therapist reads the alphabet in the order of their frequency of use in French, Bauby blinks when she reaches the letter he wants to use, thus freeing his mind to create. Over time, Bauby receives visits from assorted friends including his young children Theophile (Theo Sampaio) and Celeste (Fiorella Campanella) and his ex-wife Celine (Emmanuelle Seigner), most of whom learn the system. The visits with his kids at the seaside hospital provide the film with a tremendous humanity, as do the flashbacks with his dying father (Max Von Sydow). Those relationships are provided as complex and rich, something many sentimental affliction films neglect.

We don’t always know what to make of Bauby, whether to like him or not for his obvious narcissism and past choices; we learn that prior to his stroke Bauby experienced a full on mid-life crisis, leaving his family for a younger woman and buying an expensive convertible. But the movie escapes cliché by not simplifying the man in order to win us over. Even late into the story, after his ex shows unwavering support in her visits, taking dictation and reading to him, a call from his estranged girlfriend shows Bauby still desperately in love. It is the wife who must communicate for Bauby. The pain on her face is another of the film’s heart breaking moments. She, along with Claude (Anne Consigny), an assistant provided by his publisher, had been diligently taking painstaking dictation for his memoir. Everyone around him is invested in the belief that he will overcome his circumstances. Nobody wants the memoir to end in fear of what that might mean.