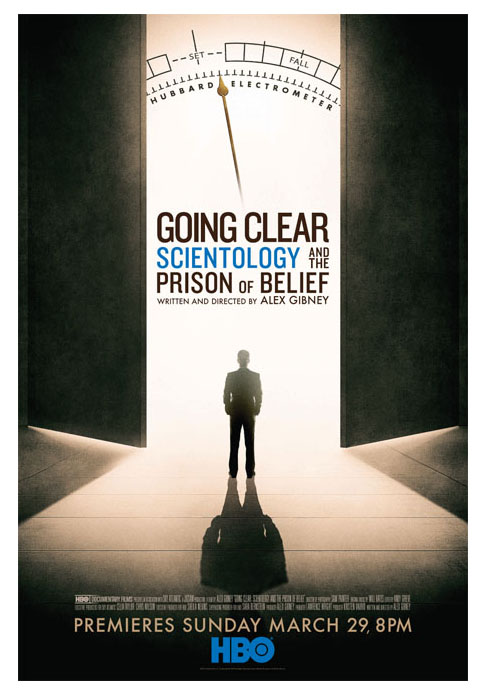

HBO’s documentary division has had a great two months. First, “CITIZENFOUR,” the documentary they produced about NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden won an Oscar and was broadcast on the channel the day after the ceremony. Then, the critically acclaimed six-part true crime series “The Jinx” ended with new evidence (and a possible confession) that got its millionaire subject Robert Durst arrested again, giving the series enormous publicity and probably many new non-appointment viewers. And now, premiering in a theatrically limited release as well as on HBO this Sunday, March 29 at 8pm ET/PT, Alex Gibney’s documentary “Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief,” has garnered a huge amount of buzz from both festival screenings and an attack campaign conducted by the film’s controversial subject: the Church of Scientology. The film is based on Lawrence Wright’s similarly titled 2013 book, “Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief.” An investigative reporter for New Yorker magazine, Wright is also the author of the 2006 Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11,” which was also turned into a documentary for HBO. The book and film tell the story of L. Ron Hubbard, a man with a colorful background, made even more colorful by his constant confabulations; a man who holds the Guinness World record for the number of books published by a single man (over a thousand), who wrote a huge bestseller called “Dianetics” in 1950 which inspired a movement ultimately called “Scientology.”

The only experience with Scientology I’ve had myself was once in midtown Manhattan chatting with a pretty girl who stood behind a table with holding an e-meter, a pseudo-scientific measuring device invented by Hubbard. She was offering free audit sessions for prospective members. (Filmmaker Oliver Stone remarks in the film that the pretty girls at the meetings were the main reason he was once a member.) As the eight ex-Scientologists in Gibney’s film testify, part of the lure of the church is that in the introductory levels—which many members never graduate from—is that it indeed seems like a benign mix of self-help tips and amateur psychoanalysis that may very well have a positive impact on people. Also key to the rise of Scientology was its establishment of Celebrity Centers, posh venues in Los Angeles and other locations that courted and catered to the needs of high profile celebrities like John Travolta and Tom Cruise, both long time Scientologists.

After Hubbard’s death in 1986, his successor David Miscavige took over and his purported exploitative behavior is central to the doc’s critique. The former members, including filmmaker Paul Haggis, interviewed in the doc describe a pattern of intimidation and exploitation of its members and harassment of anyone who dares to investigate the Church. When the IRS tried to revoke their tax-free status as a religion, Miscavige is said to have directed members to sue individual IRS agents in order to bring them to the bargaining table. The most harrowing parts of the film describe claims that senior members who displeased Miscavige were often imprisoned in a hard labor facility called the hole. One woman tells the story of being cut off from her entire family when she decided to leave the Church. One critical absence in the film is any defense by the Church itself. They have subsequently claimed to have offered up 35 staff members for Gibney to interview but say he refused to speak with them. The Church has also set up an entire section of their website to condemn and reply to the documentary.

Wright has said that he didn’t start out to expose Scientology, only to understand why people join the movement. He and Gibney certainly demonstrate its appeal and the subsequent difficulties many have had leaving the church, but the absence of anything other than occasional titles stating things like “Tom Cruise has denied this” make the film conspicuously one-sided, no matter how compelling the testimony of Haggis and the others, or how petulant much of the copy on the Church’s website may be. Even so, “Going Clear” is another great achievement for the prolific Gibney (who already has two new docs—one about Frank Sinatra for HBO and another about Steve Jobs that just screened at SXSW). At two hours long it drags a bit during the second hour but it’s otherwise a riveting, highly intelligent look into an organization that few people understand, one whose keen exploitation of human insecurities and desires speaks volumes about many other, larger systems of belief.